What’s up, beloveds?

Today, I bring to you one of my most favorite English-language contemporary poet writing in the US. Sarah Ghazal Ali. Her debut poetry collection, Theophanies, is a certified work of genius. Ali complicates faith and religion, centers womanhood and matrilineage, and contends with the lyric—all the while displaying ethereal and sublime language.

I urge each and every one of you to read her work.

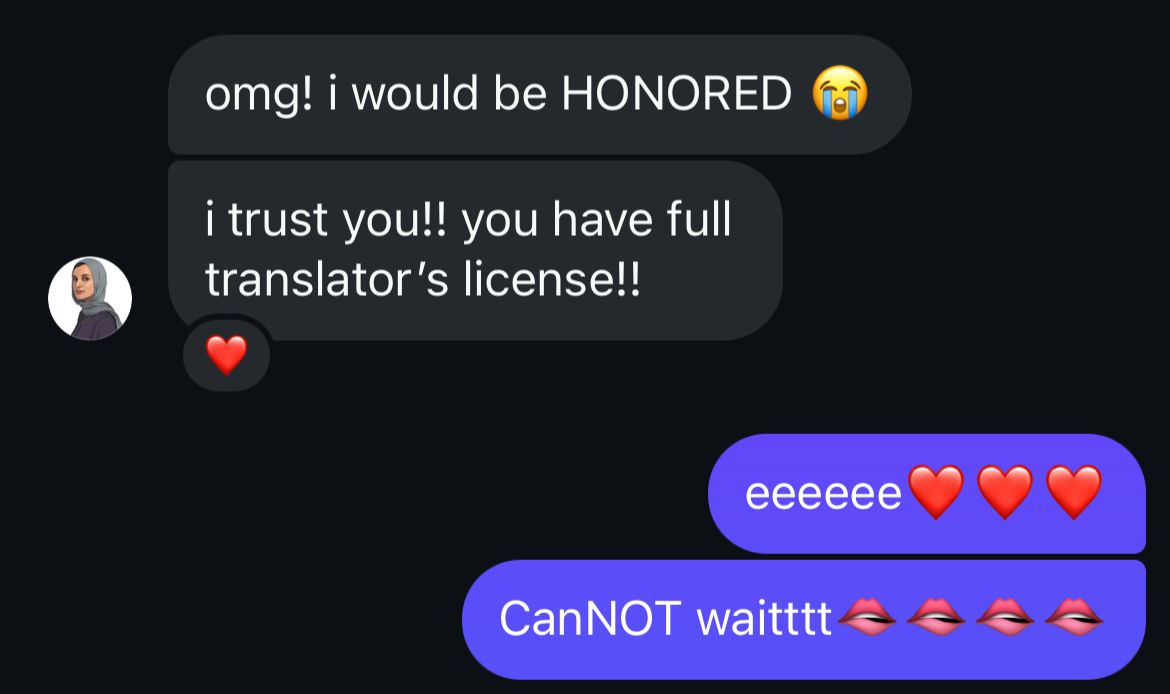

And so, it gives me immense pleasure that I have mother’s blessings and permission to translate her poem, NUDE, here.

NUDE was first published by The Boiler here.

NUDE by Sarah Ghazal Ali that first August, blood dotted linoleum an apple bared its wayward stench I sucked my finger & tested a clipped word on my tongue then a blush a kitchen performance an approximation of American freedom can anything private be vulgar? then what use of my feckless mouth? God simmered below the limen of sight even the apple brought here by force & forced then to fit malus domestica the domestication of sin I lived briefly unwitnessed touched only by evening shadows my silhouette caressing the door

Translation

In order for more people to access my translation, I have decided to also include a transliterated version of the Urdu text, aka Roman Urdu. Below, you will find both the audio and roman versions of the translated poem.

Transliteration

be-pardah woh pehla agast, farsh par khoon ki boondein aik saib ki be-raah mehek mein ne apni ungli choosi aur aik katay hue lafz ko apni zabaan par parkha phir sharm baawarchi-khanay mein tamasha Amriki aazadi qareeb par duur kya kuch niji fahash hosakta hai? phir mere be-kaar mun ki kya auqaat? khuda parday ke peechay sansana raha hai jabran laya hua saib bhi, aur jabri milaya hua malus domestica gunah ko gharelu banana unn dinon, meri gawahi dene wala koi nahi tha sirf shaam ke saaye mujhe chhutay thay aur mera siyah khaaka darwazay ko choomta tha

You can listen to my translation here:

Notes on Translation

The form of the poem—including its caesura—appears as the original.

The title, “Nude,” encapsulates so much in the original—an idea, an image, a color, a portraiture. The initial two options I was weighing for the title were: “ننگی” (nangi / naked) and “جسم” (jism / body). “Naked” felt distinct from the body of the poem (standing out), while “body” didn’t seem to encapsulate the tone of the poem well (ineffective).

It was then that I returned to the idea rather than the image. The concept of “limen” in the line about God in the poem gave me permission to talk about the concept of “purdah” or “veil.” God is beyond sight (behind the veil), but the speaker is violating sight (unveiled). Thus, I went with “بے پردہ” (be-pardah / uncovered).

I love the different shades of red present in the original poem: blood, apple, blush. I kept apple and blood, but translated “blush” as not a color, but an emotion: “شرم” (sharm) which is both a cause for reddening (literally, shyness) and the Urdu word to refer to one’s genitals.

I believe American freedom contains a connotation in the English-language that is missing from its literal translation: امریکی آزادی (Amriki aazadi). I struggled with this bit. Any thoughts? Suggestions?

I am usually thinking about tenses during translation, and I was thinking about it more so through this poem.

The line, “God simmered below the limen of sight” is in the simple past tense. And although being in the past, it conveys a feeling of continuity. However, in translation, I change it into the present continuous tense:

“خدا پردے کے پیچھے سنسنا رہا ہے” because “ہے” (hai / is) instead of “تھا” (tha / was) felt more urgent and continuous, as the poem demanded.

Another line where I changed the tense of the poem is the last line, “my silhouette caressing the door”

In the translation, it is in the same tense as the line that precedes it (past continuous) to maintain the continuity offered in the original.

I spent a significant time thinking about how to translate the line, “I lived briefly unwitnessed”. Because the poem has minimal punctuation, the word associations are interpretive and multiple, i.e. briefly could belong to lived or to unwitnessed or to both (which is the interpretation I have). So, this meant: “I lived briefly” and “briefly unwitnessed” was both possible and probable.

This line also reminded me of Momin Khan Momin’s couplet:

تم مرے پاس ہوتے ہو گویا

جب کوئی دوسرا نہیں ہوتا

About which my professor, Asif Iftikhar, said that it contained eight different meanings, depending on which word you stressed in the couplet.

(Also a fun-fact: Mirza Ghalib is said to have offered his complete Divan (book of poetry) for this couplet of Momin’s.)

Add to this: I went back and forth on how to translate unwitnessed. Two options were: شہادت (shahadat / witness) in which the word شہادت (shahadat) has another connotation: martyrdom, and “گواہی” (gawahi / witness), which has a sort of legal/textual connotation. I chose the latter.

Ultimately, I made the decision for you, the reader, to set the speaker in a finite time-space, which meant I lost out on the complexity of multiple interpretive associations.

“اُن دنوں” (unn dinon / in those days) is a nod to “lived briefly” signifying finitude, and “گواہی دینے والا کوئی نہ تھا” (gawahi dene wala koi na tha / unwitnessed) is a nod to “briefly unwitnessed.”

A question that occurred to me during this exercise—and which I want to offer to you too to groupthink—was: how does one translate menstruation in Urdu? The exact word for it is “ماہواری” (mahwari / monthly). Feelings?

Afterword + Workshop

I am certain I am still forgetting a few other things I want to say about this poem. The point is: a good poem is in layers, like an onion (I am picking up this analogy from another poet, I am cursed to be forgetting exactly whom and where)—but like an onion, there are things to be enjoyed on a surface-level, upon one read, but like an onion, it will also allow you to peel back the layers—if you sit with it long enough—and reveal more images, connections, associations, etc not evident in the first reading.

I am certain I will have more things to say about this poem much later on.

While you’re here,

I am offering an online, 4-week generative workshop in June on The Grotesque and The Abject. You can check out more information and register here. We will be reading more poems like NUDE, involving blood, the sacred and the carnal, and food.

Thank you to Sarah for writing this poem, for allowing us to read and bask in its beauty. Thank you for reading and engaging with my translation.

Until next time,

Javeria

This Reminded me of a famous misra “hum ne be parda tujhay parda nasheen daikh lia”. Thats what you did to the poem.

Agar exam main sirf aik sawal hota k iss angraizi nazm ka tarjuma karein; main bhag jata, but you did a great job, i know the pain one has to go through, coz there is always something which is “lost in translation”.

oh wow i always resonate with a poem more deeply when i reread it after reading your translation of it! translating nude as bepardah here was genius.

also this made me want to know the 8 interpretations of the momin couplet :(